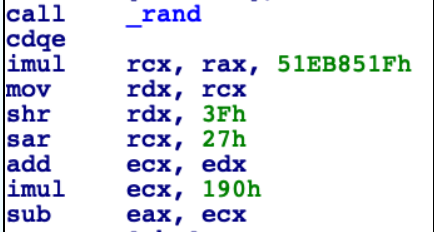

Yesterday, I was reversing an app and came across the following instruction snippet:

If you've spent enough time staring at compiler-optimized assembly, you know that this is performing a division-by-multiplication. The reasoning behind this is that on many processors, the divide instruction is many times slower than the multiplication instruction. With some wacky math (which I'll try to explain in this post), we can divide by a constant with a combination of multiplications and right shifts (which are also fast).

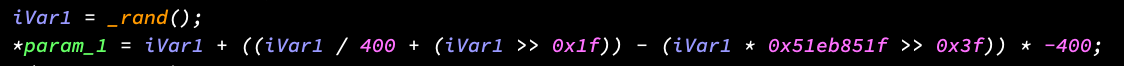

Now I normally use Ghidra when reversing because decompiler ez. Ghidra knows about this optimization so the correct division will be shown in the decompiler window. However, even Ghidra (partially) fails with this code.

You can see that Ghidra picks up on the correct divisor (400) but given that this specific listing is a slight variation of the common optimization, we get the extra cruft on the end that makes it unintelligible.

I've been trying to get better at down-and-dirty assembly reversing anyways so let's go through this listing, instruction by instruction, to see what's going on.

The Trick

Before proceeding, I should probably explain how we can divide by a constant this way. For reference, here's a great blog about the topic if you find my explanation lacking. And for good measure, here's another good but much more mathematically rigorous explanation.

One key to this trick is the fact that right shifting is the same as dividing by a power of two. (I'm going to assume that the reader is already familiar with this).

It's important to note here that the division from a right shift is actually a division followed by a floor operation (the kind of integer division you'd expect in C) since we don't care about the least significant bit before the operation (the remainder). For example, 3 = 0b11 >> 1 = 0b1 = 1 = floor(3/2) and we get the same result as if we were performing 2 = 0b10 >> 1 = 0b1.

The rest of the trick follows logically from this: we find a constant to multiply our dividend by so that if we divide by a power of two (right shift), we get the desired result. The hard part is finding the aforementioned constant and proving that we'll get the exact same result as the actual division. As I am but a simple man, I won't cover any proofs here; there's plenty of that in the articles previously linked.

Finding the Constant

Skipping ahead to the solution, we see that the constant (denoted as m) comes out to be 2^(32+l) / d where d is the divisor and l = floor(log2(d)).

Before we unpack that, we can confirm that to get the desired result, we just need to right shift our dividend (n) multiplied by m:

n * m = n * 2^(32+l) / d => (n * m) >> (32+l) = floor(n / d)

Perfecto!

I'm not rock-solid on the reasoning behind the exponent (32+l) but I believe it's because it gives us an approximation with enough precision that the result is guaranteed to be accurate.

Think about why we don't just calculate n >> l. d can be anywhere from 2^l to 2^(l+1) which can be quite a large range as l increases. Therefore, the shift result could vary wildly from the desired quotient.

As we increase the exponent, the change in d in proportion to the whole exponent gets smaller. And since we're assuming that d is 32-bit number, l < 32 and can never dominate the 32 term. Again, that's a very off-the-cuff explanation but it sounds OK to me.

A detail I skipped over is that to perform the integer multiplication, m must first be converted into an integer. To do this, we take the ceiling. I don't have an informal explanation for this but the math is clear (take a look at the ridiculousfish article for deets). Therefore, our final expression for m is ceil(2^(32+l) / d).

Variations

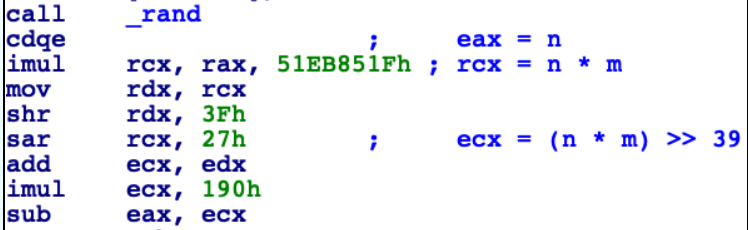

Using our new knowledge, let's partially annotate the motivating code listing:

Looking at the sar instruction, we guess that l should be 7 since 32+7 = 39 = 0x27. However, we can try all possible d's between 2^7 = 128 and 2^8 = 256 and none of them result in an m of 0x51eb851f. What gives?!

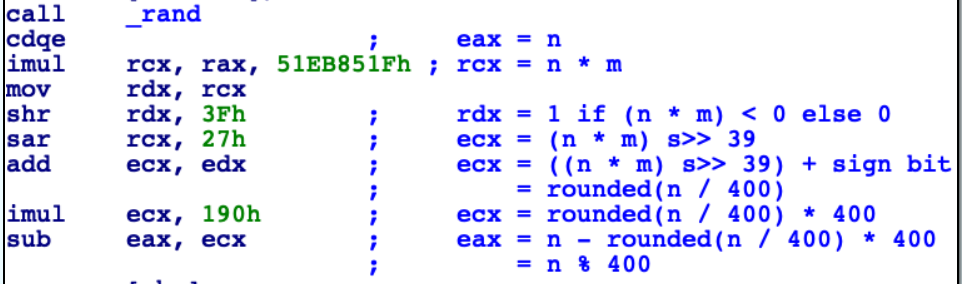

Well the answer lies in the fact that the shift instruction is sar instead of shr. sar fills in the most significant bits of the result with the sign bit of the input. This (and the instructions that I conspicuously didn't annotate) are a dead giveaway that we are actually performing signed division! After all, rand returns an int, not an unsigned int.

The second imul instruction serves as a hint as to what d actually is, namely 0x190 = 400. That imul and the subsequent sub also tell us what the code snippet as a whole might be doing:

int r = rand();

r -= (r / 400) * 400;

or more simply,

int r = rand() % 400;

Let's emulate the code snippet in Unicorn (yes this is overkill but this whole endeavor is overkill) to test our hypothesis. Bet you didn't think you'd learn how to learn Unicorn in this post, did ya.

We start by initializing an emulator and writing the code into its memory:

from unicorn import *

from unicorn.x86_const import *

with open('/Applications/SuperSecureApp.app/Contents/MacOS/SuperSecureApp', 'rb') as f:

data = f.read()

code = data[code_start:code_end]

addr = 0 # Arbitrary address to place the code in the emulator.

mem_size = 1024 * 1024 # Unicorn only let's map in 1Mb chunks.

mu = Uc(UC_ARCH_X86, UC_MODE_64)

mu.mem_map(addr, mem_size)

mu.mem_write(addr, code)

Then we'll pick a bunch of random 32-bit integers, initialize eax to that random value, emulate the code, and assert that the resulting value in eax is eax_orig % 400.

for _ in range(100):

eax = random.randint(0, 0xffffffff)

mu.reg_write(UC_X86_REG_EAX, eax)

# Reset rcx and rdx as well since they will be overwritten in the code.

mu.reg_write(UC_X86_REG_RCX, 0)

mu.reg_write(UC_X86_REG_RDX, 0)

# Convert eax to a signed integer.

eax = as_signed(eax)

# Python's modulo operator only returns positive numbers, so we'll subtract

# the modulus (400) if eax is negative to get the negative modulo result.

expected = eax % 400 - 400 * (eax < 0)

# Run the emulation.

mu.emu_start(addr, addr + len(code))

# Read out the value of eax as a signed integer.

eax = mu.reg_read(UC_X86_REG_EAX)

actual = as_signed(eax)

assert expected == actual, 'Expected %d. Was %d' % (expected, actual)

print('Saul Goodman')

We need to do a little bit of fiddling to get it to work with negative numbers but if we run it, we can see that the code is indeed performing rand() % 400.

For the curious, here's the as_signed function:

import struct as st

def as_signed(x, fmt='I'):

return st.unpack(fmt.lower(), st.pack(fmt, x))[0]

OK, but how does it work?

To answer the titular question, we need to think in more detail about how division works in C.

When performed on unsigned operands, the result is indeed the floor of the quotient. However, when the result is negative, the end result is actually the ceiling of the quotient. Therefore, the result of a division in C is the quotient rounded to zero.

If we think about what we already have from the previous steps (that is floor(n / d)), we can achieve the desired result by simply adding one whenever (n / d) < 0. That is because when (n / 2) >= 0, floor(n / d) is already the desired result. And since the ceiling of a number if just one plus the floor, adding one to a negative quotient, results in ceil(n / d).

Now we can finally annotate those missing instructions:

What about m?!

Now that we know how the algorithm works, only one burning question remains: how do you get 0x51eb851f from d = 400?

To do that, we need to rework our formula for m in the unsigned case.

Previously, m = ceil(2^(32+l) / d). But now that we're dealing with signed integers (two's complement to be specific), we shouldn't add 32 to l since then we run the risk of making m negative. This is because the most significant bit (the 63rd bit in this case), is the sign bit which tells the CPU whether or not a number is negative (the actual encoding is slightly more complex).

Regardless, now the most we can exponentiate two by is (31+l). And if we calculate what m should be:

d = 400

l = int(floor(log2(d))) # l = 8

m = ceil(2**(31+l) / d)

print(hex(m))

we indeed get 0x51eb851f.

Conclusion

I hope you found this post spiritually fulfilling. I personally hate this kind of stuff but have the utmost respect for whoever came up with this trick. I can't even fathom how one generates something like this. As always let me know what I got wrong or what I could've done better in this post (I'm sure there's a lot in this one). Cheers.