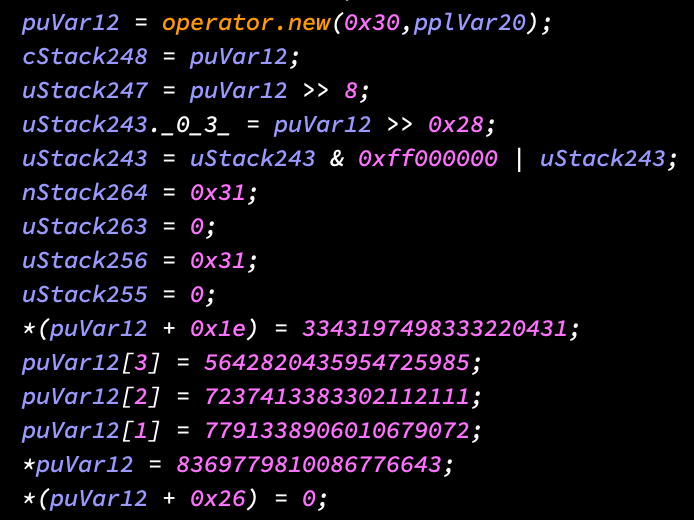

In this post, I'll be discussing a method I recently implemented to have stack strings show up in Ghidra's decompiler window. The final script transforms this garbage:

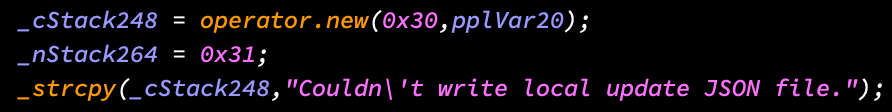

into this significantly better garbage:

Let's get into it. There's a link to the code in the conclusion.

Background

If you've seen my Medium, you know that I like looking at the Spotify binary. I continued this trend recently since I had a problem with my Skiptracing project. Every so often, I would notice that I wasn't getting new skips recorded from the MacOS client. I ran otool -L and my skip tracing dylib was nowhere to be found!

After some investigation, I came to the conclusion that Spotify must be updating itself in the background and overwriting the binary. This was supported by the fact that I had an IDA database in /Applications/Spotify.app/Contents/MacOS that disappeared when the skips stopped as well. Spotify is probably just wiping this whole directory.

Anyways, I began to investigate functions that referenced interesting, updated-related strings and to my horror, I saw the aforereferenced stack strings. (As an aside, this technically isn't a stack string since the pointer is allocated using new but I'll just be calling them stack strings since it's easier).

What is this boost/C++ bullshit? I actually don't know a good reason why this would show up in non-malware. Seriously, if anyone knows, email or tweet me.

Hopefully I'll write a blog post on the update process soon but for now, I couldn't live with myself if I let this live in the decompiler. Let's squash this.

Identifying the Problem

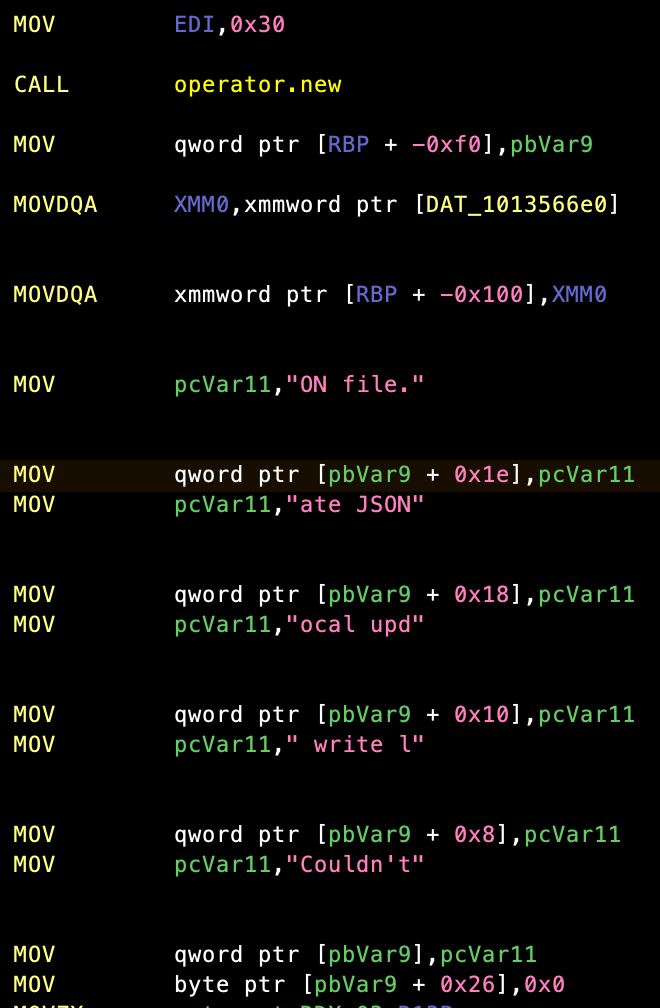

Let's take a look at the assembly that generated our garbage stack string:

This is made a little harder to read by way of galaxy-brained Ghidra renaming registers so let's go through it step by step.

Allocate the string

mov edi, 0x30 ; allocate 0x30 bytes

call operator.new

mov qword ptr [rbp - 0xf0], rax ; store the pointer to the buffer at rbp - 0xf0

Some C++ bullshit

The next two instructions move two quadwords onto the stack just before our buffer pointer. I assume this has to deal with some sort of class member initialization for std::string but I'm not sure. I really, really hate C++ reverse engineering. Again, if anyone knows, let me know.

Create the string

mov rcx, <packed chars>

mov qword ptr [rax + offset], rcx

This repeats several times until we finally write the null terminator:

mov byte ptr [rax + offset], 0x0

Now, we could write some instruction regex's and that would be all good and well, but looking at other stack strings in the function, there are some peculiarities that make this difficult.

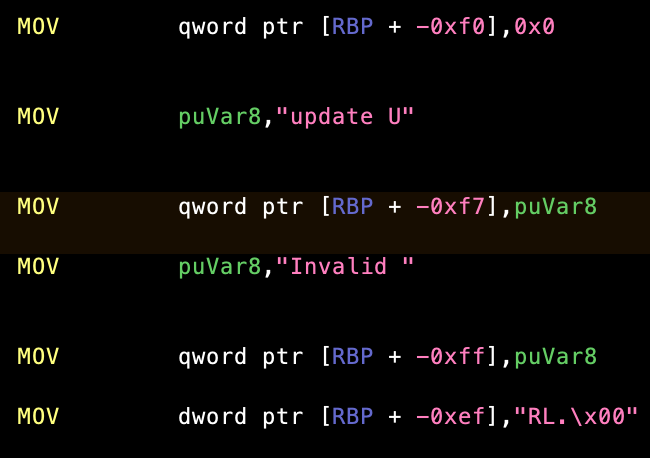

For example, some of the stack strings are actually stack strings, that is they're built on the stack:

Therefore, we'll want to be handle to handle multiple pointer registers. In addition, in the above example, "RL." is moved as a double word, including the null-terminator, so we can't assume that a part of the string is all printable ASCII.

Now all this could probably be done with some complicated regexs, but who likes writing regexs? Let's have some fun with everyone's favorite IL, pcode! (Another advantage of using pcode is that the stack string detection bit is architecture-independent!)

A Gentle Introduction to Pcode

Pcode, Ghidra's IL, is a register transfer language. This means that operations like load, store, add, etc. all take their inputs/send their outputs to "registers". I say "registers" in quotes because they aren't aren't just the architecture's registers like RAX and RDI, but an abstraction for all of the machine's memory.

Since it's still important to know whether or not data is in a machine register or ram, each pcode memory location, known as a varnode, has an associated address space. This address space represents where the memory is located, like ram for ram, register for a machine register, or const for an immediate value among others.

Take a look at the official Ghidra docs for a better explanation.

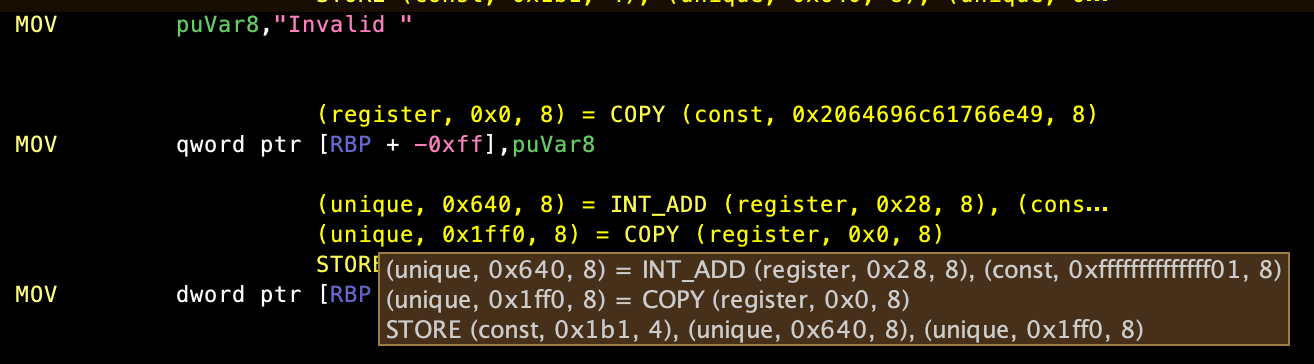

Now that we kind of know what pcode is, let's look at the pcode for our stack string building instructions:

Let's deconstruct the two instructions pictured.

mov rax, "Invalid "

This instruction is translated into a single pcode COPY operation. COPY, as you might expect, copies the memory specified by the varnode on the rhs into the varnode on the lhs.

We now get a good look at how a varnode is represented. For example, the destination for the COPY, rax, is represented as:

(register, 0x0, 8)

This illustrates how each varnode is basically a 3-tuple composed of an (address space, offset, size). For rax, it is a machine register, so it goes into the register space. It is also the first register in Ghidra's processor definition (this is arbitrary) so it's offset is 0, and rax is a 64-bit register, so the size of the varnode is 8 bytes.

Looking on the rhs, we can see that our packed chars are represented as:

(const, <big long hex string>, 8)

The peculiar thing to note is the offset for this varnode. For constant varnodes, the offset is the immediate value. I feel like overloading the offset field makes some operations more difficult to understand but what do I know.

mov qword ptr [rbp - 0xff], rax

We see that this instruction is actually translated into three pcode operations: an INT_ADD, a COPY, and a STORE. Let's go over each operation.

First we have (unique, 0x640, 8) = INT_ADD (register, 0x28, 8), (const, -0xff, 8). The INT_ADD operation, as one would expect, adds the two operands. The first operand is a register with offset 0x28, which corresponds to rbp and the second operand is a constant like we saw before.

The output is something we haven't seen before, a varnode in the unique address space. The unique space is sort of a scratch space where temporary values (like an offseted-register) are stored.

The next operation is a COPY. This should look familiar. The only difference between this COPY and the previous one is that the source is a register instead of a constant.

Finally, there's a STORE operation. The second and third inputs are pretty intuitive: the second input is the destination and the third input is the data to store. In this case, the destination is at offset 0x640 in the unique space. Looking at the first operation, this is where rbp - 0xff was stored. The data is taken from unique 0x1ff0, where rax was copied into.

The unintuitive parameter is the first one. This is the space ID of the destination varnode. To be honest, I'm not 100% sure as to why the space of the destination varnode isn't this value, but that's just the way it is. I think it might be an ID for the memory block in Ghidra (i.e. ram) but I feel like I've seen mixed results confirming this. Regardless, we don't care about it. Get it out of here!

Detecting Stack Strings with Pcode

To detect/recover stack strings, we'll emulate the function (semi-symbolically) and then detect COPY's of long ASCII strings followed by a STORE. Here's a gif simulating this for part of the string "Couldn't write local update JSON file." to help visualize:

We start by initializing some data structures (dictionaries in Python) to keep track of the register and unique varnode spaces. Then for each pcode operation, we'll try to evaluate it's inputs in our current context.

If our varnode is in the const space, we can just take its offset. Otherwise, we'll have to hope that we previously stored something in that varnode's space and offset.

If it's not, then we'll have to evaluate the varnode symbolically, like RAX in the example above. We now have to keep track of the register name and offset to that register in the same output varnode, e.g. (unique, 0x620) in the example above.

When we execute a STORE to this address, we store the portion of our stack string in "ram" at the symbolic register + offset. Then when subsequent portions of our string are moved into "ram", we can merge the two locations if they are overlapping (as can be seen in the last frame of the gif).

Patching the Program

After playing around a little bit with setting data types in the decompiler, I reached the conclusion that Ghidra's decompiler just wasn't built to handle this situation (and I don't blame them -- that'd be pretty crazy if they could account for this). After some thought, I decided that the best way forward was to patch the program with some assembly that Ghidra would know how to interpret.

Let's take a second to talk about what that assembly might look like.

What to Patch With

We need something where it is obvious to Ghidra that we are moving a string into our target register and offset. What better way than calling strcpy? Our plan will be to:

- Write the string into memory.

- Call

strcpywith our reg + off as the destination and stack string as the source.

Things get a little tricky when you start to consider where to place the string.

We could try to put it at the end of the __text or __data section since then we'd have to shift around all of the subsequent sections to make room. Doable but not great.

We also could create a new section after all of the existing sections and put our strings there. The problem with that is that if we actually want to run the binary after patching it, we'll need to add a new load command to the Mach-O header. Again, doable, but a lot of unnecessarily work involved.

The obvious answer as to where to put our strings is in the code that was used to create them! The one caveat is that we'll need to jump over each string so we don't try to execute it.

Here's how we'll structure it, assuming our stack string is at [reg + off]:

push rsi ; save all the registers we're going to use

push rdi

push rax

lea rsi, [0x9] --- ; get our string address into the source register

--- jmp strlen + 2 | ; jump over the string

| s <----

| t

| a

| c

| k

|

| s

| t

| r

| i

| n

| g

| \x00

--> lea rdi, [reg + off] ; get our register + offset into the destination register

call strcpy ; call strcpy

pop rax ; restore the registers we used

pop rdi

pop rsi

This patch is fine if a little long. Remember that all of this needs to fit in the space of the instructions used to construct the stack string. Therefore, there are a few optimizations we can make to make our code shorter.

The first we can make is if our offset is 0 (which is the case for our strings in registers allocated by new). If the offset is 0, we can change:

lea rdi, [reg + off]

to

push reg

pop rdi

We save a whopping 1 byte with this!

Here's another massive 2 byte optimization we can make if our register is in rax (which again is the case for strings allocated by new).

Since strcpy returns the destination pointer in rax, we don't need to save and restore rax. Therefore, we can change

lea rdi, [reg + off]

to

pop rdi

since rax was the last item pushed onto the stack, if we pop, we get our destination pointer into rdi. Since rax is no longer on the stack, we can also get rid of the pop rax instruction after calling strcpy.

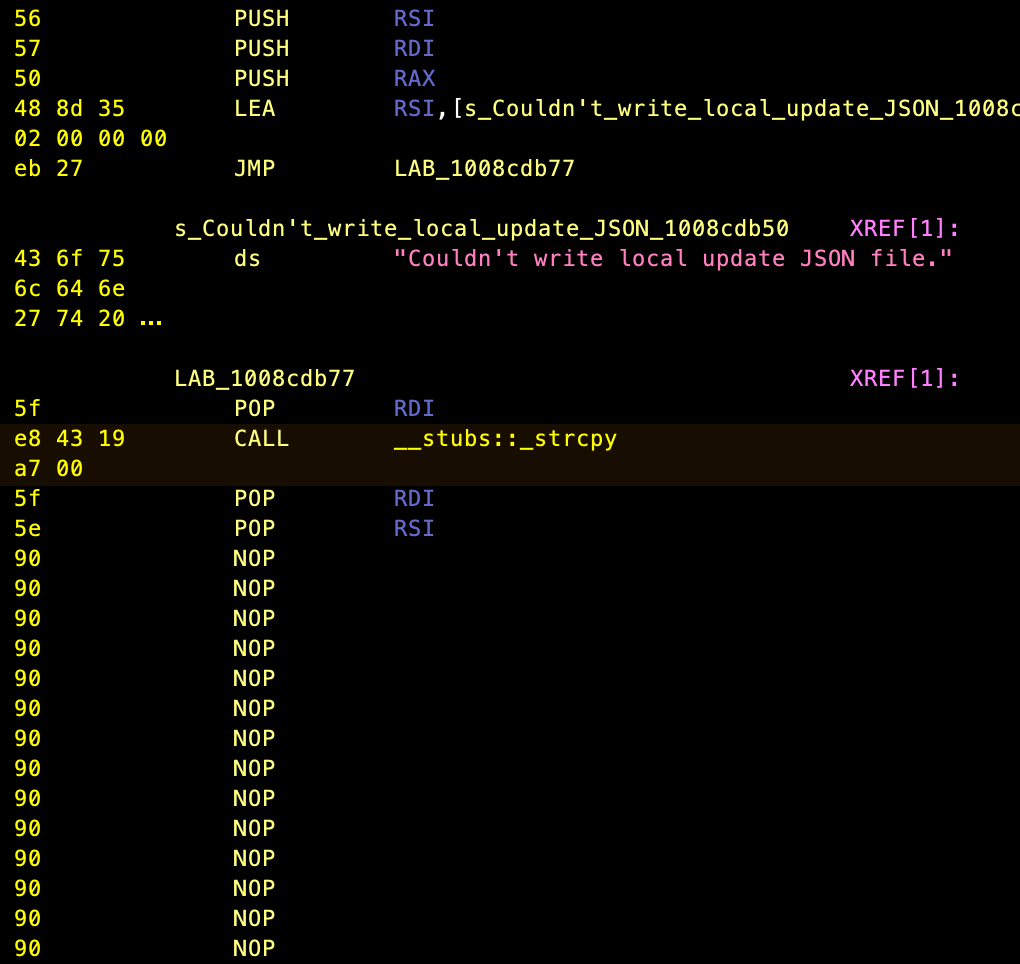

Let's take a look at how the assembly looks after patching it:

Looks nice! Even better in the decompiler!

Conclusion

All in all, this was a pretty fun foray into pcode and patching to help the decompiler. I probably spent way too much time doing this for the benefit it gives me but what the hell! I learned something and I hope you did too!

As a reward for making it this far, here's a link to the code. It's very gross and hacked together at the moment so consider yourself warned. I'd be extremely shocked if it worked out of the box for your application. Maybe if people actually want to use the project, I'll clean it up.

Let me know what you think.