How many flies are in my apartment?

Recently, I was sitting on my fire escape with the window to my apartment slightly open. As there are no screens, I wanted to keep it as closed as possible to keep out any bugs. However, I needed to keep it somewhat open so that I'd be able to get back indoors.

As it was a hot, smelly day in New York City, the flies were abuzz. I found it hard to relax on my illegal balcony knowing that I was basically inviting all of the flies into my apartment for an all-you-can-eat buffet of human detritus.

This got me thinking how effective the partially closed window is at keeping out the flies. What does the function of flies in my apartment over time look like? The perfect question for a Sunday afternoon when you have no friends (unless you count the flies).

How does a fly... fly?

In order to run this simulation, we need a model of how a fly navigates its trash-filled world. As a first pass, I'll model a fly as moving in a random direction with a random speed for each timestep of the simulation. Pretty simple, but flies do appear to be relatively simple creatures.

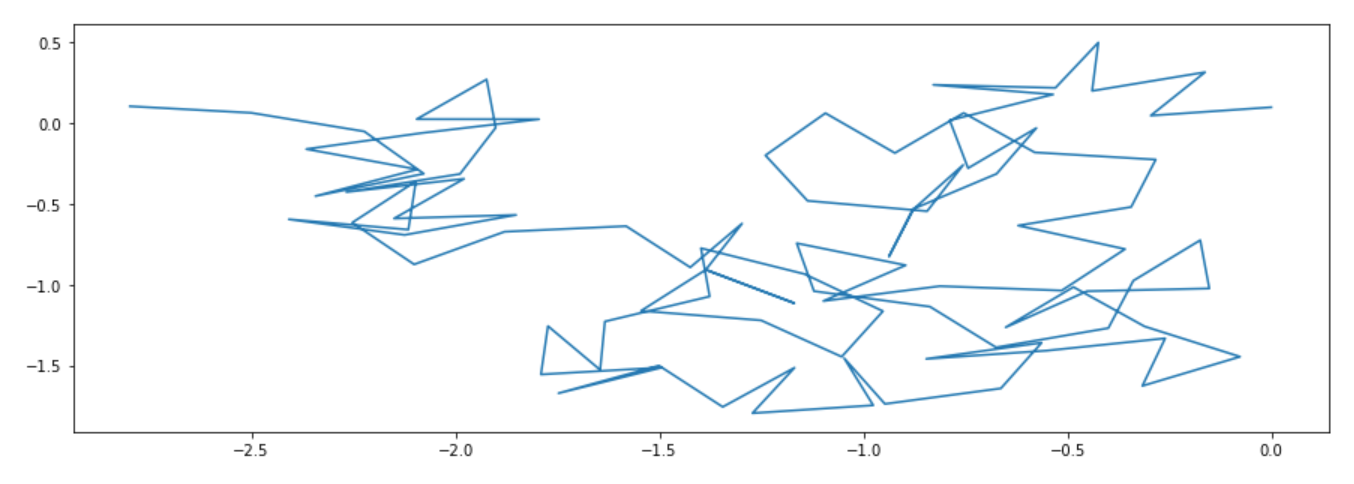

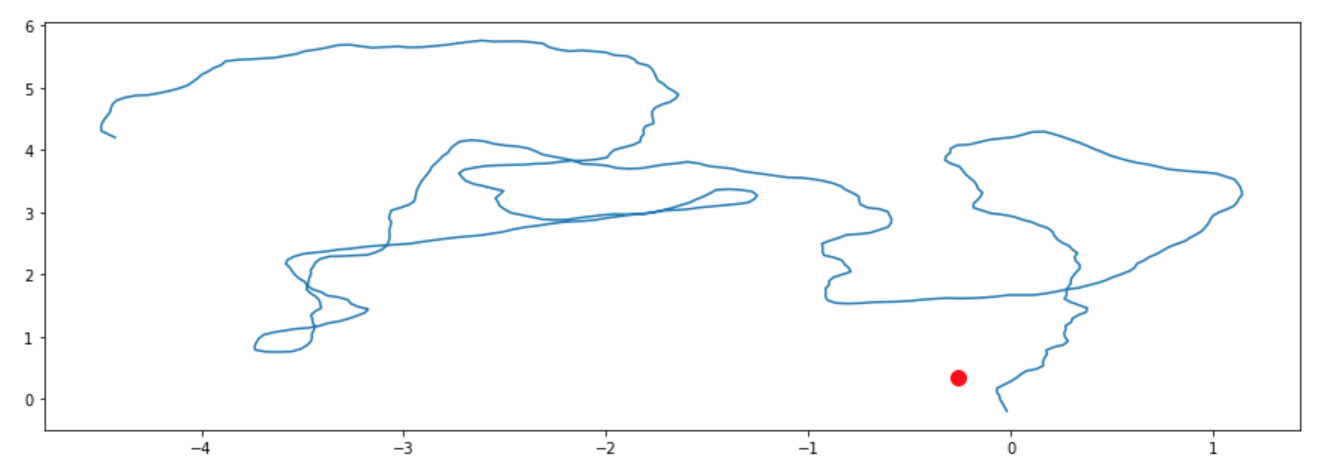

If we take a look at the trajectory of a single fly using this model, it does indeed look random:

Now let's simulate a bunch of flies. To do this, first we initialize an array xs to hold the position of the flies. We'll normally distributed this in a 2*WORLDHEIGHT x WORLDHEIGHT square. We'll also initialize all the flies to be outside (setting the window to be at x = 0 and indoors to be x > 0).

xs = np.random.randn(NFLIES, 2) * np.array([[WORLDHEIGHT * 2, WORLDHEIGHT]])

xs[(xs[:,0] > 0),0] *= -1

xs[(xs[:,1] < 0),1] *= -1

Then we'll create another array vs to hold the velocity vectors of the flies.

vs = np.random.randn(NFLIES, 2)

vs = vs / np.sqrt((vs ** 2).sum(1)[:,np.newaxis]) * maxv

Then we'll have an update function like so:

def update(xs, vs):

# 1. Propagate the flies.

xps = xs + vs * dt

# 2. Make sure flies can't go through the glass.

inoutmask = (np.sign(xps[:,0]) * np.sign(xs[:,0])) == -1

m = (xps[inoutmask,1] - xs[inoutmask,1]) / (xps[inoutmask,0] - xs[inoutmask,0] + 1e-7)

b = xps[inoutmask,1] - m * xps[inoutmask,0]

invalidmask = b > WINDOWHEIGHT

idxs = np.where(inoutmask)[0][invalidmask]

xps[idxs,0] = 1e-4 * np.sign(xs[idxs,0])

xps[idxs,1] = b[invalidmask]

# 3. Bound the flies.

xps[(xps[:,0] > WORLDHEIGHT),0] = WORLDHEIGHT

xps[((xps[:,1] > WORLDHEIGHT) & (xps[:,0] > 0)),1] = WORLDHEIGHT

xps[(xps[:,1] < 0),1] = 0

# 4. Set the new positions and velocities.

xs = xps

vs = np.random.randn(NFLIES, 2)

vs = (vs / np.sqrt((vs ** 2).sum(1)[:,np.newaxis])) * maxv

return (xs, vs)

Step 2 might require a little explaining. Every timestep, each fly travels in a line from its previous position to its new position. We only want the flies to be able to travel through the crack at the bottom, so we need a way to ensure they can't travel through the glass.

To do that, we first find all of the flies that changed indoor/outdoor state this timestep (inoutmask). This can be done by comparing the sign of the previous and current x since the window is at x = 0. We can then calculate where the fly crossed the line x = 0 using some middle school math.

It should be impossible for the fly's y-intercept to be greater than the height of the window crack, we for thos flies (invalidmask), we set their y to be where they tried to cross the window and their x to be some small epsilon on the side that they came from. I don't just set it to 0 because then the fly would not get picked up by inoutmask and may be able to travel through the glass on the next iteration.

Step 3 just makes sure that the fly does not go through the arbitrary walls of the world. Currently, only the floor and the walls of my apartment are defined so a fly can escape to infinity in the -x or +y directions while outdoors. Here's a diagram of the world for the visually-inclined:

---------------- y = h

| |

| |

| |

|

_________________________________|

x = -h x = 0 x = h

OK, we can finally see the flies fly! Because of the random velocity vectors, they unsurprisingly look quite jittery:

Thankfully, it looks like not too many flies made it indoors.

Smoothness

This is great and all but the flies don't look too realistic. Let's make their velocity vectors vary smoothly so that they don't look like a dubstep light show.

To do this, we'll pick a random angle in the range [-pi/8, pi/8] to rotate each fly's velocity vector by. In this simulation, we won't vary the magnitude of their velocities at all.

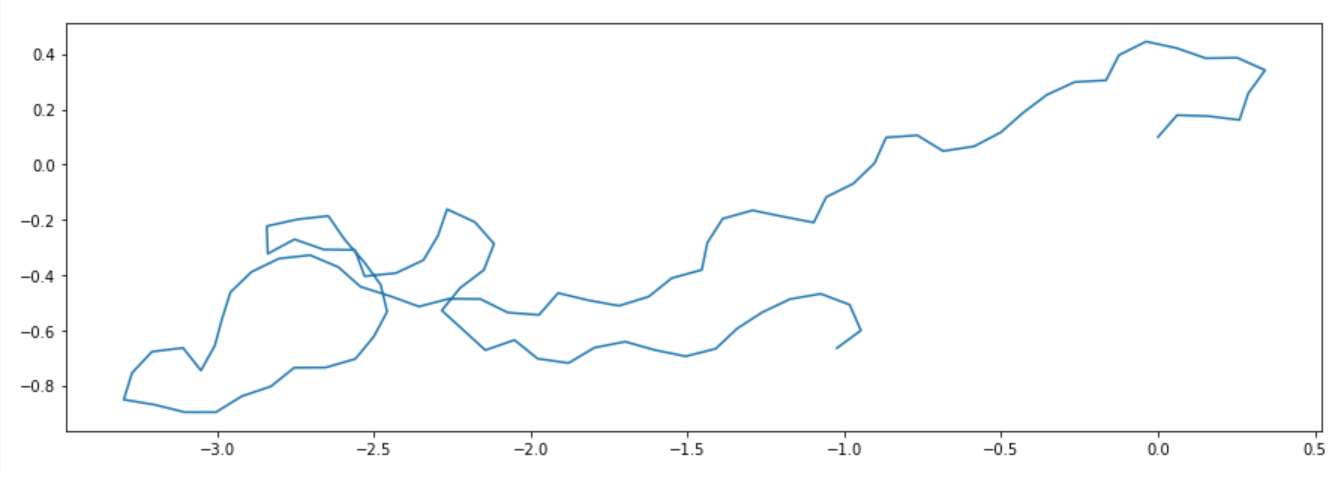

Let's look again at how this changes the trajectory of a single fly:

We only need a couple of changes to our update function:

def update(xs, vs):

...

# 2. Make sure flies can't go through the glass.

...

# 2.5. Flip the x-velocity of the invalid flies.

vs[idxs,0] *= -1

# 3. Bound the flies.

...

# 4. Set the new positions and velocities.

...

dthetas = np.random.randn(NFLIES) * np.pi / 8.

Cs, Ss = np.cos(dthetas), np.sin(dthetas)

Rs = np.array([[Cs, -Ss], [Ss, Cs]]).transpose(2, 0, 1)

vs = (Rs * vs.reshape(NFLIES, 2, 1)).sum(axis=1)

While not necessary, Step 2.5 was added so that the flies don't take get stuck keep trying to go through the window as their velocity rotates slowly.

In Step 4, instead of choosing new random values for vs, we create a random rotation matrix for each fly and rotate their initial velocities by it.

If we take a look at the animation now, we can see the flies look slightly more realistic (if not still a bit spazzy):

Attraction

While the flies now obey the laws of aviation, there's still something that seems missing. Normally, flies want to get indoors. They need to get indoors. So to simulate this, I added an attractor (maybe a rotting piece of fruit) at a position A indoors to lure the flies.

To do this, I added one variable to the fly's state: a scalar value a which represents how close they are to the delicious piece of fruit. The fly will be able to remember the most recent value of a so that it can know whether it's getting warmer or colder.

Again, we only need to make a few changes in order to simulate this:

def attraction(x, A):

return 1. / (1e-7 + np.sqrt(((x - A.reshape(1, 2)) ** 2).sum(1)))

def update(xs, vs, ats):

# 1. Propagate the flies.

...

ats = attraction(xs, A)

atps = attraction(xps, A)

# 4. Set the new positions and velocities.

...

dthetas = np.random.randn(NFLIES) * np.pi / 16.

wrongmask = atps < ats

dthetas[wrongmask] += np.random.randn(wrongmask.sum()) * np.pi / 8.

...

return (xs, vs, ats)

The rules for rotating the velocity are simple:

- If the attraction increased from the previous timestep, keep going in the same direction (do nothing)

- Otherwise, rotation by a random angle in the range of

[-pi/8, pi/8]

We add another random rotation in the range of [-pi/16, pi/16] just to keep things interesting.

The fly will keep going in a straight line (with some random jitter) as long as the attraction it sense is increasing. If it senses that it's going in the wrong direction, it will more aggressively explore its neighborhood until it finds a good direction to head in.

As you can see by the new trajectory, this seems to work fairly well for simulating a stupid but well-motivated fly:

However, it seems on the aggregate, the flies just swarm the attractor. Thankfully this isn't the case in real life as I currently only have two flies in my apartment.

Statistics

With this information in hand, I finally wanted to answer the popular game show question: "How many flies are in my apartment?"

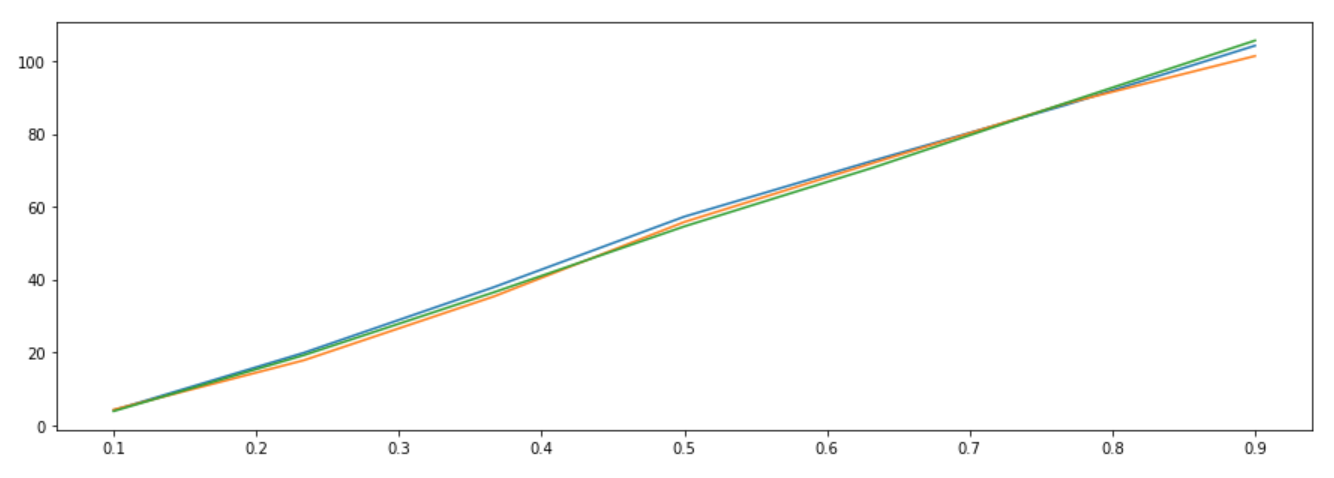

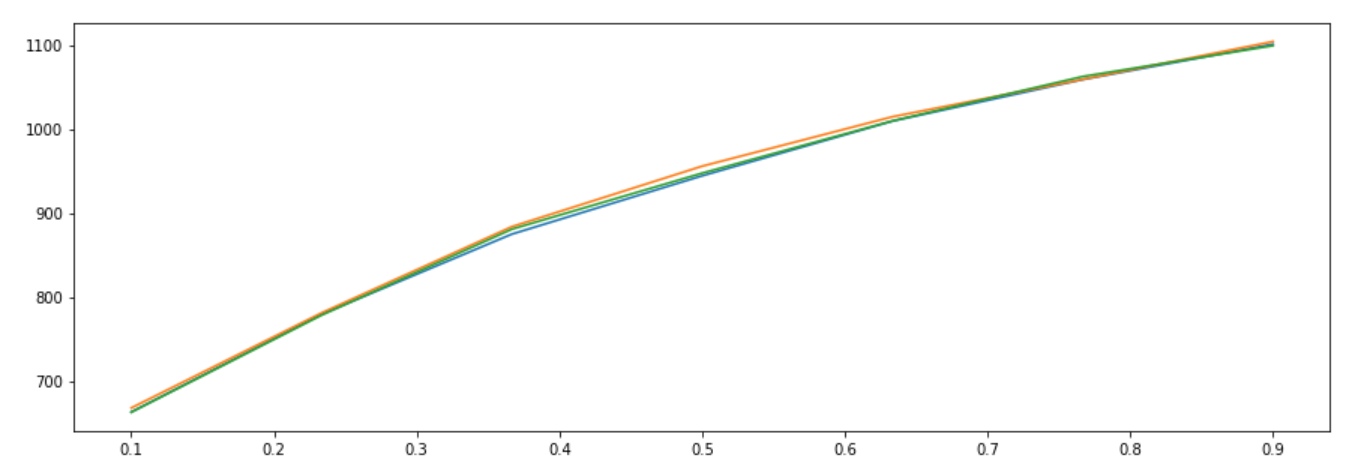

The first experiment I ran was to plot the average number of flies given how open the window was over a few max velocities. Here is the result for the random flies:

Quite nicely, it turns out that as the window, gets more open, the number of flies indoors increases linearly.

For the smooth flies, we see a less linear function. I'm not quite sure why.

The attracted flies produce an even more asymptotic (is that a word?) plot. My hypothesis is that this is because the flies are more likely to find their way to the trash than in other models so it doesn't help them as much when the window is more open.

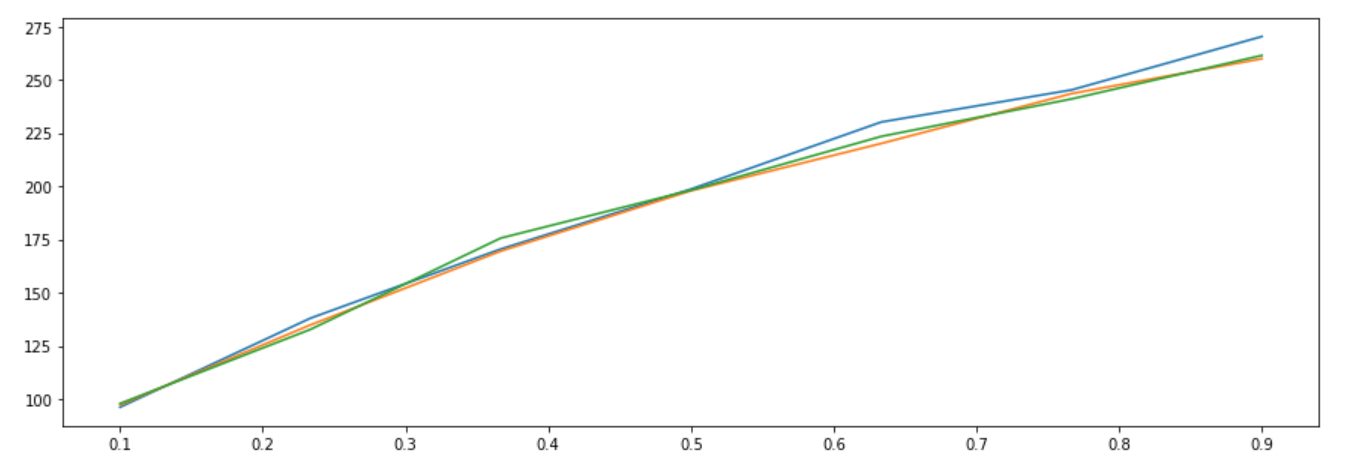

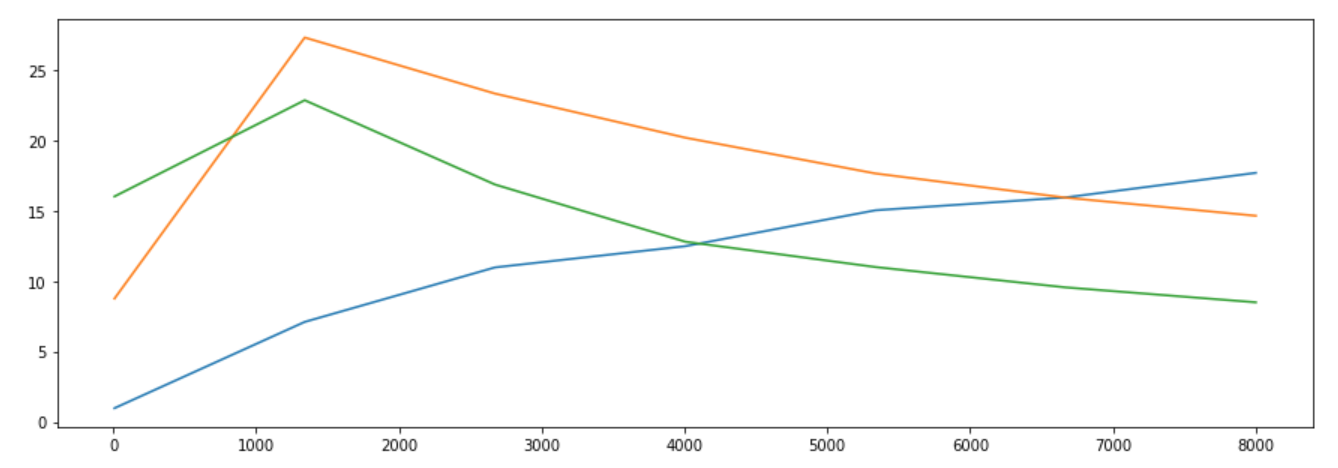

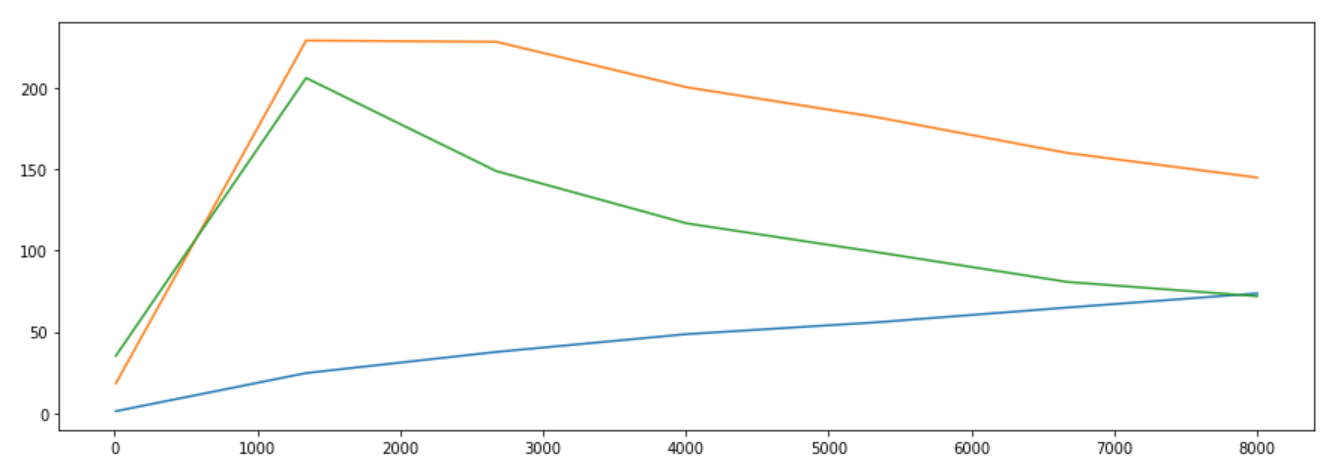

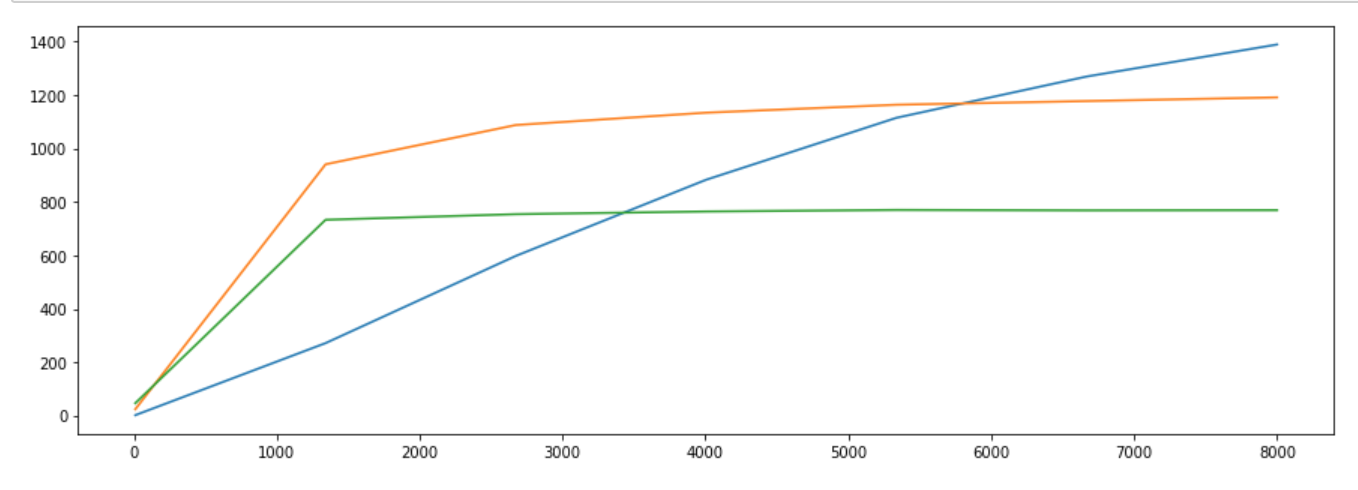

Then I wanted to see how long the simulation ran for affected the number of flies. We see similar results for the random and smooth flies. With faster moving flies (the orange and green plots), random moving or in the smooth case randomly initialized flies are more likely to barrel off towards infinity when outside. Therefore, the total number of flies decreases as the simulation progresses.

In the case of the attracted flies, we again see that a higher max velocity results in the number of flies peaking earlier. However, because the flies have some knowledge as to what direction to go in, they tend not to drift out into the ether and the population eventually plateaus.

Conclusion

Thanks for joining me on this pointless exerise and in case you missed it the answer to the titular question is two. Their names are Buzz and Neil.